在之前的文章中,我们详细介绍了如何使用 tar 命令创建存档。虽然 tar 是Linux(Linux)的一种非常常见的压缩方案,但它在Windows和Mac OS X用户中并不那么受欢迎,他们会发现他们的大部分档案都是使用 zip 格式创建的。

在Linux中使用(Linux)Zip(创建)和Unzip(扩展)档案很容易。事实上,大多数GUI归档管理程序(例如Ark、File Roller和Xarchiver)将充当您计算机上几乎所有命令行归档程序的前端,Zip也不例外。当然,我们也可以从终端使用(Terminal)Zip。就是这样。

正如您可能猜到的那样,第一步是打开终端(Terminal)。

接下来,输入“ sudo apt-get install zip unzip ”(不带引号),以确保我们安装了 zip 和 unzip。

注意:如果这两个程序已安装,您将收到一条消息,说明情况如此,如上所示。(Note: if those two programs are already installed, you’ll receive a message stating this to be the case, as shown above.)

安装后,我们可以使用 zip 创建存档(或修改现有存档),然后解压缩以将其展开为原始文件。为了本文的目的,我们将在桌面(Desktop)上创建一个名为Stuff的新文件夹。在终端(Terminal)中,我们可以使用单个命令来执行此操作 - mkdir /home/username/Desktop/Stuff(当然,您可以将“用户名”替换为您自己的用户名,如下所示,如果您已经有一个Stuff文件夹在您的桌面(Desktop)上,您需要更改名称)。

现在我们有了一个Stuff文件夹,我们将使用“cd”命令将Stuff文件夹设置为我们当前的工作目录。

cd /home/username/Desktop/Stuff

现在,在终端中输入(Terminal)touch doc1.txt doc2.txt doc3.txt && mkdir Files,这将创建一个名为Files的文件夹,以及三个文档 - doc1.txt、doc2.txt 和 doc3.txt - 在Stuff文件夹中.

还有一个命令,将“cd”到新创建的Files 文件(Files)夹(cd Files),因为我们需要其中的一些其他文件。

光盘文件(cd Files)

最后,键入touch doc4.txt doc5.txt doc6.txt以创建三个新文档。

现在,键入cd ../..将桌面(Desktop)更改回工作目录。

在创建 zip 文件之前,我们的倒数第二步是在桌面(Desktop)上创建几个与我们刚刚创建的文件同名的“额外”文档,因此键入touch doc2.txt doc3.txt来创建它们。

最后,打开这两个“额外”文本文件中的每一个并向它们添加一些文本。它不需要任何有意义的(或长的),只是为了让我们可以看到这些文档确实与已经在Stuff和 files 文件夹中创建的文档不同。

完成后,我们就可以开始创建我们的 zip 文件了。使用 zip 最简单的方法是告诉它您要创建的 zip 存档的名称,然后明确命名应该进入其中的每个文件。因此,假设我们的工作目录是Desktop,我们将键入zip test Stuff/doc1.txt Stuff/doc2.txt Stuff/doc3.txt以创建一个名为 test.zip 的存档(我们不需要使用“.zip ”命令中的扩展名,因为它将自动添加),其中将包含在Stuff文件夹中找到的 doc1.txt、doc2.txt 和 doc3.txt。

您会看到一些输出,它告诉我们三个文档(doc1.txt、doc2.txt 和 doc3.txt)已添加到存档中。

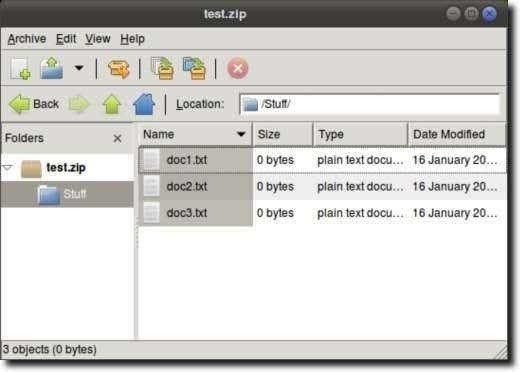

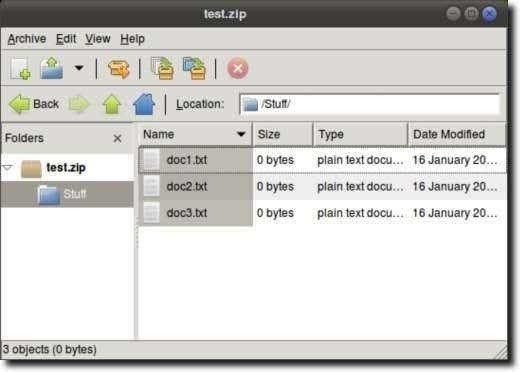

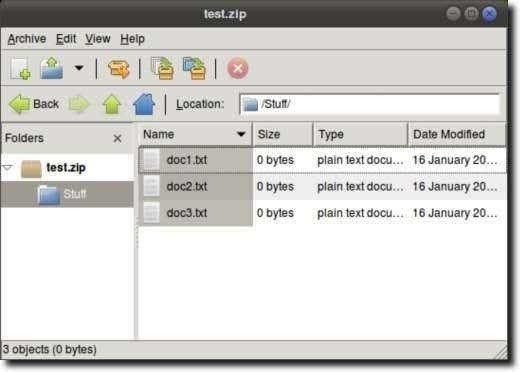

我们可以通过双击存档来测试它,它应该位于我们的桌面(Desktop)上。这样做应该在标准存档程序中打开它(KDE中的Ark、GNOME中的File Roller和Xfce中的Xarchiver)。

现在,Files 文件夹呢?假设我们想要它,将其中的文档也添加到我们的存档中,我们可以使用与上面相同的命令,但将Stuff/Files/*添加到命令的末尾。

星号表示包含文件夹内的所有内容。因此,如果 Files 文件夹内有另一个文件(Files)夹,它也会被添加。但是,如果该文件夹中包含项目,则不会包含这些项目。为此,我们需要添加-r(代表递归或递归)。

需要注意的是,上述两个命令并非旨在将文件“添加”到 zip 存档中。它们旨在创建一个。但是,由于存档已经存在,该命令只是将任何新文件添加到现有存档中。 如果(Had)想要一次创建这个存档(而不是我们为了教育目的而逐步添加文件的三个步骤),我们可以简单地输入zip -r test Stuff/*并创建相同的存档。

您会从命令和输出中注意到Stuff文件夹中的三个文件以及Files 文件(Files)夹中的三个文档都包含在内,因此一切都通过一个漂亮、简单的命令完成。

现在,我们在桌面(Desktop)上创建的那两个“额外”文档呢? 好吧(Well),zip 的工作方式是,如果您尝试将文件添加到存档中已经存在的存档中,新文件将覆盖旧文件。因此,由于我们在桌面(Desktop)上创建的文档(doc2.txt 和 doc3.txt)都有内容(我们在 doc2.txt 中添加了“hello world!”,在 doc3.txt 中添加了“yay”),我们应该能够添加这些文档,然后就可以进行测试了。 首先(First),我们将两个“额外”文档拖到Stuff文件夹中。

系统可能会询问您是否希望新文档覆盖现有文档(请记住,这是在文件夹中,而不是 zip 存档),所以让它发生。

现在完成了,让我们通过键入zip test Stuff/doc2.txt Stuff/doc3.txt

您会注意到上面的命令现在显示正在更新而不是添加的文件。如果我们现在检查存档,我们会注意到文件看起来是相同的,但是当打开 doc2.txt 和 doc3.txt 时,您会看到它们现在有内容,而不是像我们的原始文件一样是空白的是。

有时在Linux中,您会看到通过在文件名的开头添加句点 (“.”) 来隐藏某些文件。这对于需要存在但通常不可见的配置文件尤其常见(这可以减轻混乱,并降低配置文件被意外删除的可能性)。我们可以很容易地将这些添加到 zip 文件中。 首先(First),假设我们要从目录中的每个文件中创建一个名为备份的 zip 文件。我们可以通过在终端中输入zip backup *来做到这一点。

这将添加所有文件和文件夹,尽管这些文件夹中的任何项目都不会包括在内。要添加它们,我们将再次添加 -r,以便zip -r backup *成为命令。

现在我们快到了。要递归添加文件夹、文件和隐藏文件,命令其实很简单很简单:zip -r backup 。

现在,解压缩非常容易。然而,在我们做任何事情之前,先删除桌面(Desktop)上的文档(doc2.txt 和 doc3.txt)以及Stuff文件夹。一旦它们消失,键入unzip test.zip会将我们原始压缩存档的内容展开到您的当前目录中。

注意:如果我们没有删除文档,我们将尝试将 zip 文件的内容解压缩到现有文件中,因此会询问我们是否要替换每个文档。

就是这样!压缩和解压缩(Unzipping)是一项非常常见的任务,虽然肯定有可用的GUI选项,但通过练习,您会发现从(GUI)终端(Terminal)执行相同的任务也不是很困难。

Create and Edit Zip Files In Linux Using The Terminal

In a previous article, we detailed how to use the tar command to create archives. While tar is a νery common compression scheme for Linux, it isn’t nearly as popular for Windows and Mac OS X users, who will find most of their archiνes created using the zip format.

It’s easy to use Zip (to create) and Unzip (to expand) archives in Linux. In fact, most GUI archive management programs (such as Ark, File Roller and Xarchiver), will act as a frontend to pretty much any command line archiving program you have on your computer, and Zip is no exception. Of course, we can also use Zip from the Terminal. Here’s how.

The first step, as you might guess, is to open the Terminal.

Next, type “sudo apt-get install zip unzip” (without the quotes), just to make sure we have zip and unzip installed.

Note: if those two programs are already installed, you’ll receive a message stating this to be the case, as shown above.

Once installed, we can use zip to create archives (or modify existing ones), and unzip to expand them to their originals. For the sake of this article, we’ll create a new folder on our Desktop, called Stuff. In the Terminal, we can do so with a single command – mkdir /home/username/Desktop/Stuff (of course, you’ll replace “username” with your own username, as shown below, and if you already have a Stuff folder on your Desktop, you’ll want to change the name).

Now that we have a Stuff folder, we’ll use the ‘cd’ command to make the Stuff folder our current working directory.

cd /home/username/Desktop/Stuff

Now, type touch doc1.txt doc2.txt doc3.txt && mkdir Files into your Terminal, which will create a folder called Files, as well as three documents – doc1.txt, doc2.txt and doc3.txt – inside the Stuff folder.

One more command, to ‘cd’ into the newly-created Files folder (cd Files), because we’ll want some other documents inside that.

cd Files

Finally, type touch doc4.txt doc5.txt doc6.txt in order to create three new documents.

Now, type cd ../.. to change the Desktop back to the working directory.

Our next-to-last step before creating a zip file is to create a couple “extra” documents on the Desktop with the same names as files we just created, so type touch doc2.txt doc3.txt to create them.

Finally, open each of the two “extra” text files and add some text to them. It doesn’t need to be anything meaningful (or long), just so we can see that these documents are indeed different from the ones already created inside the Stuff and files folders.

Once that’s done, we can start creating our zip files. The simplest way to use zip is to tell it the name of the zip archive you want to create, then explicitly name each and every file that should go into it. So, assuming our working directory is the Desktop, we would type zip test Stuff/doc1.txt Stuff/doc2.txt Stuff/doc3.txt to create an archive called test.zip (we don’t need to use the “.zip” extension in the command, as it will be added automatically), which would contain doc1.txt, doc2.txt and doc3.txt as found inside the Stuff folder.

You’ll see a bit of output, which informs us that three documents (doc1.txt, doc2.txt and doc3.txt) have been added to the archive.

We can test this by double clicking the archive, which should be sitting on our Desktop. Doing so should open it up in the standard archive program (Ark in KDE, File Roller in GNOME and Xarchiver in Xfce).

Now, what about the Files folder? Assuming we want it, add the documents inside it, into our archive as well, we could use the same command as above, but add Stuff/Files/* to the end of the command.

The asterisk means to include everything inside the folder. So if there had been another folder inside the Files folder, it would have been added as well. However, if that folder had items inside of it, they will not be included. To do that, we would need to add -r (which stands for recursive or recursively).

It should be noted that the above two commands aren’t designed to “add” files to a zip archive; they’re designed to create one. However, since the archive already exists, the command simply adds any new files into the existing archive. Had wanted to create this archive all at once (instead of the three steps we’ve performed to gradually add files to it for educational purposes), we could simply have typed zip -r test Stuff/* and would have created the same archive.

You’ll notice from the command and the output that the three files inside the Stuff folder are included, as well as the three documents inside the Files folder, so everything was accomplished in a nice, simple command.

Now, what about those two “extra” documents we created on our Desktop? Well, the way zip works is if you try to add a file to an archive that already exists in the archive, the new files will overwrite the old ones. So, since the documents we created on our Desktop (doc2.txt and doc3.txt) have content to them (we added “hello world!” to doc2.txt and “yay” to doc3.txt), we should be able to add those documents and then be able to test this. First, we’ll drag the two “extra” documents into the Stuff folder.

You’ll likely be asked if you want the new documents to overwrite the existing ones (this is in the folder, remember, not the zip archive), so let this happen.

Now that this is done, let’s add them to the archive by typing zip test Stuff/doc2.txt Stuff/doc3.txt

You’ll notice the above command now shows files being updated instead of added. If we now check the archive, we’ll notice the files appear to be the same, but when doc2.txt and doc3.txt are opened, you’ll see they now have content in them, instead of being blank as our original files were.

Sometimes in Linux, you’ll see that some files are hidden by adding a period (“.”) to the beginning of the file name. This is particularly common for configuration files, which need exist, but often aren’t visible (which eases up on clutter as well as makes it less likely a configuration file will be accidentally deleted). We can add these to a zip file quite easily. First, let’s assume we want to create a zip file called backup out of every file in a directory. We can do so by typing zip backup * into the Terminal.

This will add all files and folders, although any items in those folder will not be included. To add them, we would add -r again, so that zip -r backup * would be the command.

Now we’re almost there. To recursively add folders, files, and hidden files, the command is actually very simple simple: zip -r backup .

Now, unzipping is quite easy. Before we do anything, however, go ahead and delete the documents on the Desktop (doc2.txt and doc3.txt) as well as the Stuff folder. Once they’re gone, typing unzip test.zip will expand the contents of our original zipped archive into your current directory.

Note: If we hadn’t deleted the documents, we would be attempting to unzip the contents of our zip file into an existing file, so would be asked if we wanted to replace each and every document.

And that’s it! Zipping and Unzipping is a pretty common task, and while there are certainly GUI options available, with practice you’ll find performing those same tasks from the Terminal isn’t very difficult either.